What every parent should know about eating disorders

Story by guest writer Martha Watson. Photo above by Ben Blennerhassett via Unsplash.

“It’s 5:25. The room is so silent you can hear the second-hand ticking on the clock, yet the anxiety is palpable. Legs shake, knuckles crack and faces wreak tension. The dark blue covers are slowly removed from each plate, one by one, revealing the less than delectable hospital cuisine. It is dinner time at the adolescent eating disorder unit at Rogers Memorial Hospital in Wisconsin. I slowly get up from my chair and walk to the table, preparing to consume another dose of my medicine, food, that promises to heal me and allow me to live the life I dream of.

Anorexia Nervosa is one of the deadliest psychiatric illnesses, which means it is highly likely that one of the other kind, talented and ambitious girls sitting with me at this table, the girls who are my support system as I face my greatest fear six times a day, will die from their eating disorder, likely due to heart failure, suicide, or starvation.”

My daughter, Elizabeth, wrote these words at age 17, during the summer before her senior year of high school. She was diagnosed with Anorexia Nervosa at age 11, though it’s likely her eating disorder started much earlier and went undetected for years.

We had no idea of the roller coaster ride we were getting on when she was diagnosed, but we dove in. We engaged a multi-disciplinary outpatient treatment team including different specialized psychologists for her, and for us as parents, along with a dietician, and an adolescent medicine physician.

Acting quickly is vital and I would recommend that to any parent. In our case, though, Elizabeth’s eating disorder was raging and entrenched even though we were using the recommended, family-based treatment.

Over 10 years, her treatment took us from what was then our home in Michigan across the country (Milwaukee, Denver, Boston, Princeton), including 15 lengthy hospitalizations at top facilities and the services of over 50 inpatient and outpatient professionals. More than one physician on our journey told us this was one of the worst eating disorders they had ever seen.

This disease turned our family upside down – there was a black cloud over our kitchen for years as we supported her re-feeding: meal by meal, bite by bite, crumb by crumb. We battled the insurance company constantly for coverage for her treatment. One or both parents supported her during long out-of-state hospitalizations, jeopardizing our jobs and the family’s financial security.

“ED” (as we called her eating disorder) screamed at her incessantly, telling her she was fat, or non-deserving of a normal life. It consumed 90-95% of her daily brain function and robbed Elizabeth of her adolescence, yet she still graduated at the top of her high school class, was accepted to three top colleges/universities, won multiple academic awards, and pursued her interest in music as a gifted soprano.

She dreamed of changing the impact of eating disorders on society. Elizabeth was frustrated by the standard and grossly inadequate protocols for treatment of eating disorders. She aspired to become a psychiatrist, so she could impact the research into causes of eating disorders and develop new treatments and perhaps even a cure.

It was an incredibly difficult road. We had allowed her to enroll at Wellesley College in Massachusetts in 2013, hoping that allowing her to achieve her collegiate dreams would quiet the eating disorder. When we arrived for parents’ weekend in October of her freshman year, we found a walking skeleton. As a legal adult, she had signed a document preventing the school from contacting us.

We immediately sought care in Boston, and she was hospitalized there in various programs for six months prior to returning home to Michigan. She had PTSD from some of the treatment experiences she encountered as she was bounced from one program to another because there wasn’t the right care available for her.

We continued to pursue outpatient and inpatient treatment for the next few years, with continued cycles of weight gain, weight loss and medical complications. When she found out she would not be able to return to Wellesley in 2015, she attempted suicide, resulting in further hospitalization.

Elizabeth bravely fought her eating disorder for nearly half of her life. She lost her courageous battle eight years ago at age 21, ironically during National Eating Disorders Awareness Week, which this year is Feb. 26 through March 3. This is an annual campaign to educate the public about the realities of eating disorders and to provide hope, support and visibility to individuals and families affected by eating disorders.

This year’s theme is “Get in the Know.” Please take a moment to learn about eating disorders which are grossly misunderstood, very pervasive in society, with underfunded research and lack of programs and training that enable early identification and intervention.

Since Elizabeth’s death, I have dedicated myself to honoring her dreams. I’ve become an active advocate in the eating disorders space. I have lobbied for Pennsylvania state legislation and national legislation with the Eating Disorders Coalition, and I’ll return to Washington, D.C., on May 8 to continue this work.

I have been a top national individual fundraiser at the National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) annual walk for the last four years. These funds will enable further research and provide support to those seeking treatment for and information about eating disorders. I have also advised and encouraged several families on their journeys through eating disorders. Most recently, I was named to NEDA’s board of directors.

When Elizabeth passed away, she already knew four young people who had died from eating disorders. That is much too high a toll for society to bear. We need to continue to raise awareness and understanding, and ensure that eating disorders are identified early and referred to treatment quickly to save lives. I firmly believe that recovery is possible, as I have seen some of Elizabeth’s friends and others I have helped succeed in recovery.

My husband Glenn and I were lucky to have Elizabeth in our lives for 21 years. I know she walks alongside me in all the advocacy I do and that I have already succeeded in many ways. But there is still much I want to accomplish. If you suspect your child has an eating disorder, please trust your parental instincts and immediately seek help. Early intervention is key and recovery is possible.

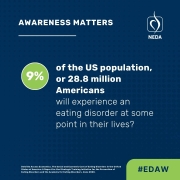

Eating Disorder Facts (learn more here)

- 9% of the US population, or 28.8 million Americans will have an eating disorder at some point in their lives.

- Eating disorders do not discriminate but affect all genders, ages, races, religions, sexual orientations, body shapes and weights.

- Eating disorders are bio-psycho-social diseases and aren’t anyone’s fault

- Eating disorders are life-threatening conditions that can affect every organ system in the body.

- There are several different eating disorders: Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, Binge Eating Disorder, Orthorexia, OSFED, ARFID, Pica, among others.

- Many who struggle with eating disorders have a co-occurring condition such as anxiety, substance abuse, OCD, depression or PTSD.

- Every 52 minutes at least one person dies as a direct consequence of an eating disorder.

- Anorexia has the second highest mortality rate of all psychiatric disorders, behind opiate addiction.

- Eating disorders can be successfully and fully treated, but only about a third of people with an eating disorder receive treatment.

- Recovery is possible but early intervention with a specialized treatment team is key.

Some signs and symptoms of eating disorders (learn more here)

- Weight loss due to excessive dieting and exercise

- Preoccupation with food and dieting

- Cycles of extreme overeating followed by purging

- Feelings of loss of control about eating

- Distortions of body image

- Skipping meals

- Extreme fluctuations in weight (up and down)

- Fear of eating in public

- Withdrawal from usual friends and activities

- Retreating to bathroom for long periods after meals

- Dizziness or fainting

- Difficulties concentrating

- Dental problems

- Gastrointestinal complaints and menstrual irregularities

Valuable resources:

NEDA Screening Tool: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/screening-tool/

Resources for Caregivers & Families:

- F.E.A.S.T (Families Empowered and Supporting Treatment for Eating Disorders): https://www.feast-ed.org/

- NEDA: https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/grace-holland-cozine-resource-center-loved-one/

- National Alliance for Eating Disorders: https://www.allianceforeatingdisorders.com/for-loved-ones/

Find Treatment & Support Groups: https://www.allianceforeatingdisorders.com/