‘Love them first and then they’ll learn’: Increasingly diverse Chartiers Valley embraces newcomers from all corners

This story is one in a series created in collaboration with the AASA Learning 2025 Alliance to celebrate the work of groundbreaking school districts in the Pittsburgh region. Kidsburgh will share these stories throughout 2023.

When the two young boys arrived at Chartiers Valley, they didn’t speak English. Their family had flown from Kuwait in crisis; their brother needed a liver transplant. As their parents spent worried days and nights at Children’s Hospital, these elementary schoolers found themselves adrift in a sea of unfamiliar faces.

It was 2013, Amanda Beckett’s first year teaching English at Chartiers Valley. In the decade since then, Beckett has become head of the district’s English Language Learners program and its first diversity and inclusion director.

But back then, she and her coworkers were starting from scratch. “The boys didn’t sleep very much,” she remembers. “They had no English at all and they had some behaviors. Sometimes they randomly walked around the building.”

So she went to their house to tutor them, and the school began helping with basic needs like winter clothing.

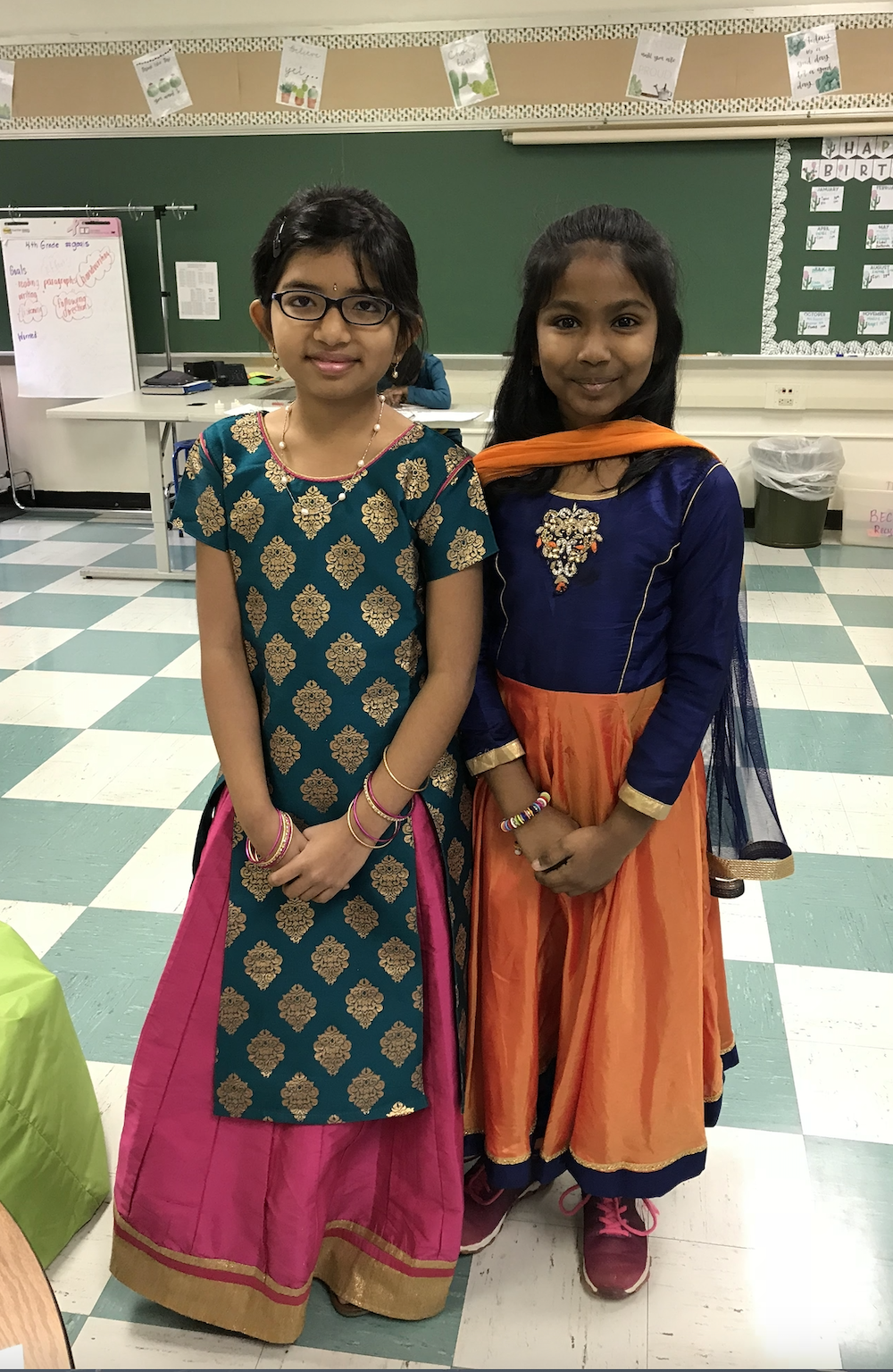

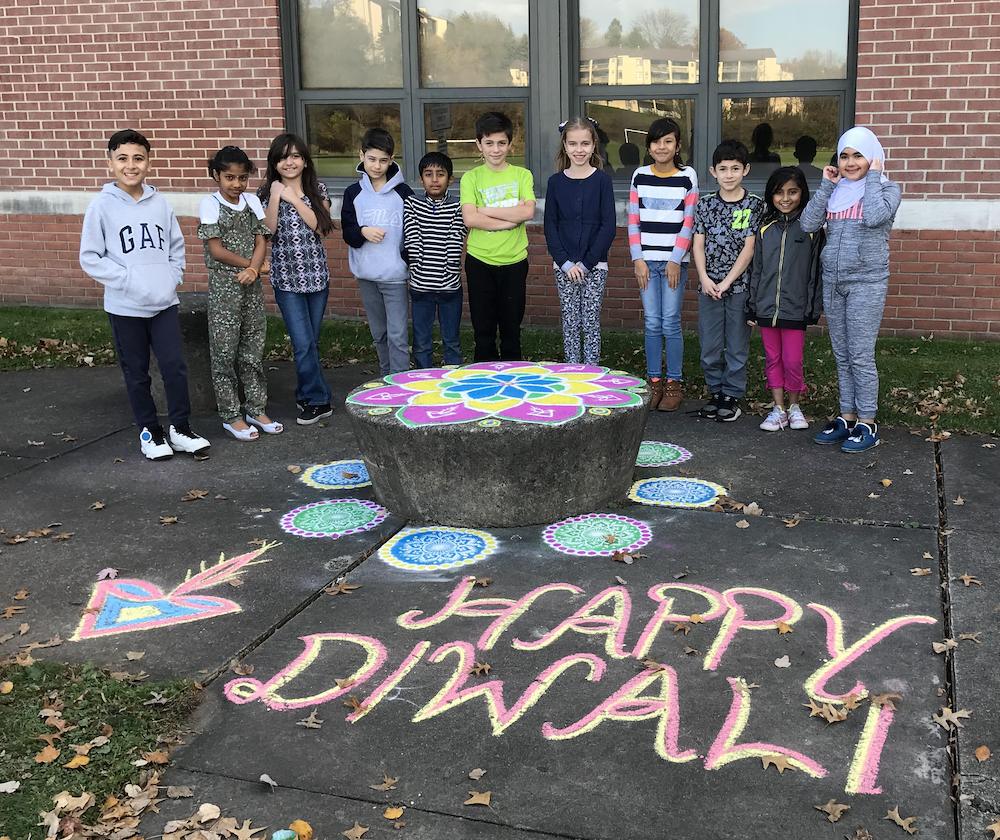

Beckett often thinks of these boys when she sees how her district now routinely rallies around new families. There are many of them: The district’s English Language Learners program teaches kids who speak 42 different native languages.

To meet this need, Chartiers Valley has evolved.

“Everything begins with relationships,” says Dr. Johannah Vanatta, the district’s superintendent.

“We have a very eclectic population that has changed exponentially over the past 10 years and includes many refugees. So it’s about forming those relationships. Are the students coming to us with trauma? Are the bells going to trigger them, if they’ve come from a war-torn country?”

A key step: connecting with the churches and nonprofit organizations that bring families to Chartiers Valley. The district also meets with new families – providing transportation, childcare, and interpreters.

“They can ask about what education will look like for their child, or what food do we serve, and how to get involved in activities at school and in the community,” Beckett says. “We also talk about needs: Do you need clothes, shoes, coats, hats? We just did a district-wide winter wear event that supported all of our families, but it especially helped a lot of our families that are new to the country. Some have never experienced winter weather.”

Chartiers Valley also opted to join the Western Pennsylvania Learning 2025 Alliance, a regional cohort of school districts working together to create student-centered, equity-focused, future-driven schools. Led by local superintendents and by AASA, The School Superintendents Association, the Alliance gives Vanatta a chance to discuss challenges and solutions with peers throughout the Pittsburgh region and nationally.

Some solutions at Chartiers Valley are relatively easy to implement, like adding hallway signage in multiple languages. Teachers have also added translation apps to their phones, and the school uses an app that sends texts in English that appear on a parent’s phone in their native language — and works in reverse, too.

Other solutions are more complex, like reassessing the school’s clearance policy to help parents who aren’t yet citizens find ways to volunteer or figuring out how to help a student who wants to play competitive sports but doesn’t yet have U.S. health insurance.

Often, the key is fostering communication across cultures. Last holiday season, a local organization dropped Christmas trees off at the homes of refugee families. That led to a few confused phone calls from folks who had never celebrated Christmas and couldn’t figure out why someone had left a tree on their front porch.

One priority for Vanatta and Beckett: Helping the school’s teachers and staff to adjust.

Teachers are also learning to research the cultures of their students.

“Why isn’t this family looking me in the eye? Because culturally, that’s a sign of respect,” Beckett explains. “Now our staff knows, ‘OK, I’m in a meeting with the mother and father but the father is the only one speaking to me. Well, in their culture, the father is the head of the household and he will do all the speaking.’ We’ve done a lot of work.”

Recently, a decade after those two young boys came from Kuwait, a set of young brothers arrived from Afghanistan. They’d been placed in an apartment but had only the clothes they’d been wearing when they left home during a humanitarian crisis.

This time, Chartiers Valley was ready.

“They had no toys, no games, no furniture. And our community stepped up,” Beckett says. “We gave them clothes and bookbags and new shoes.”

These boys are facing many challenges – ones that few longtime Pittsburgh residents have encountered. But their lives can be changed by the district’s core principle: Help everyone feel welcome.

“It’s amazing,” Beckett says. “Once they feel comfortable and safe, and have basic needs met, then the learning is going to take off. The learning will always come.”

Want to download this story? Click here for a PDF.