Play takes center stage in Pittsburgh through workshops, grant funding and community-wide playful learning

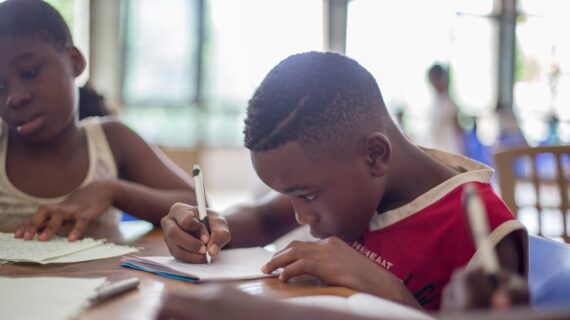

Photo above of students and educators playing together in PPS Faison by Ben Filio. This story was shared with Kidsburgh by RemakeLearning.org.

A quiet revolution is happening in Pittsburgh’s schools and communities. It involves surprises and joy, curiosity and discovery, and dozens of daily moments when students and teachers connect as human beings.

This growing movement – which couldn’t be more needed at a time when educators and students alike are dealing with all manner of challenge and stress – is all about playful learning.

Playful learning. That sounds wonderful! Everyone must love that idea…

Actually, no. It can be surprisingly challenging to convince people that play is a necessity (spoiler alert: research has proven that it is) and that it fuels learning, rather than distracts from it.

“Nobody is anti-play as a concept,” says Dahlia Rao, who spearheads the grant-funded Partners in Play initiative alongside Hatch founder Shannon Merenstein.

“All the teachers that we meet – across the board, in every school – like play as an idea,” Rao says. But many educators aren’t familiar with research showing that play is at the core of all learning. They may not know about evidence-based practices for playful learning that have been proven to be extremely valuable.

And they’re often surprised to find that “you’re not giving up math or writing or science when you’re making time for play,” Rao says. “You’re just giving it roots in the child, who actually comes to all the other subjects with more of a whole self – a more curious, more engaged self.”

In the two years since it was created through a Moonshot grant, Partners in Play has infused play into the learning experience of kindergarteners and first-graders at Pittsburgh Public Schools’ Faison and Arsenal elementary schools.

“We’ve been working with a cohort of nine teachers over the past two years to really create this protected period of open-ended, child-led play called Playlab,” Merenstein says. This year she and Rao will build on that by working with those teachers “to explore what some of those practices might look like in a math or literacy or science context.”

It hasn’t been all smiles and giggles. Not every teacher and administrator could see the potential value of Playlab when the project began. But slowly, as they saw how students responded, they “could see the connection,” Rao says.

On their own, these very young students would incorporate things they’d learned in their classroom into their Playlab experiences. And the self-directed creative experiences kids had in Playlab would surface in the classroom, helping to fuel their academic learning.

Perhaps most powerfully, this group of teachers began to discover their students as individual people.

“All the teachers have said, ‘I see the children here. I see them in ways that I don’t see them in the classroom,’” Rao says. “Everything in education says learning is based on relationships and you can’t learn if you don’t feel safe and allow yourself to be vulnerable. So the more that a teacher can see their students and the more that the students can see their teacher, it’s setting them up for more effective learning.”

During playful learning, joy is a priority. But “joy is not necessarily a synonym for ‘happy.’ It’s joy in bringing your full self to the play experience, and that’s an opportunity that many children simply just don’t have during the day when they are seen only as their sort of academic self,” Merenstein says. “And so we’ve heard from the educators that yes, this protected time and space is joyful for them in being able to be with their students in a way that’s different than the way they are the rest of the day.”

Play is an Essential – and Lifelong – Experience

Dave Bindewald, founder of the Center for Play and Exploration, understands why some adults might dismiss “play” as something expendable in our busy, stress-filled world. We have so many crises to tackle, tasks to accomplish and things to worry about.

After all, “if you’re awake or alive or conscious for even just a little bit each day,” Bindewald says, you’re likely to read about or see something tragic.

But there is good news: “That tragic thing,” Bindewald says, “is seldom the last part of the story.”

Bindewald is just as inspired by the subject of play as Rao, Merenstein and their cohort of teachers have become. He works with adults in Pittsburgh – often groups of coworkers sent to him by their employers – but he’s seeking the same kinds of creative thinking and learning that the Partners in Play team has been inspiring in elementary classrooms.

“Human work, when it’s done best, is an act of play and exploration – going looking for hidden potential, unlocking it, messing around with it to see what it could do,” Bindewald says.

At the Center for Play and Exploration, adults get reminded that in early childhood they instinctively thought creatively and divergently. They problem-solved – even if the solutions they came up with were impractical and even impossible.

So as they seek to master the 21st-century skills of problem solving, creative thinking and team collaboration that their employers (and our society) desperately needs them to harness, it’s not a matter of learning something new. It’s about reconnecting with the innately playful capacity that got taught out of them somewhere along the way.

“It’s not like your brain and your body hits a certain developmental stage or a certain age and curiosity and divergent thinking and risk taking and all that – you’re not able to do it anymore. No, those are with you forever and always,” Bindewald says. “You learned over time that they’re not valuable and those skills won’t get you anything or it’s embarrassing to be wrong, and don’t fail publicly.”

Kids start out, he says, totally willing to be playful and curious: “A child will try. A child will raise their hand and they don’t even know the rest of the question … they’ll just give it a go.” But when the opportunity to approach things playfully is absent or discouraged, “we quickly learn not to do that because of the power of shame and fear of failure.”

Playful Characteristics

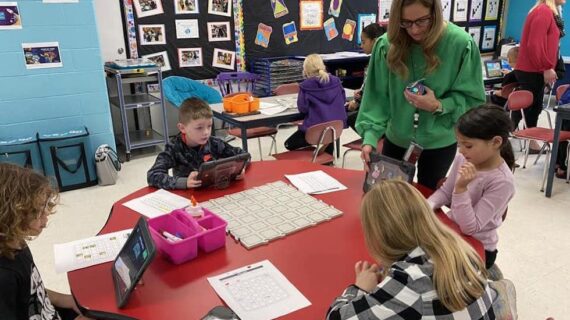

Researchers have identified certain characteristics of the types of play that promote learning for children, says Sarah Wolman, founder of Lightbulb Learning Lab. These include the presence of joy and surprise – the fun of not knowing what number will come up when you roll the dice or not knowing how an experiment will turn out, but not worrying at all about doing it “right.”

These joyful, playful experiences are even more impactful when they are social – perhaps because when you share a play experience with another person, “you’re explaining it or they’re explaining it,” Wolman says. “There’s something about the shared aspect of the play experience that actually promotes deeper learning.”

Bindewald finds this when he works with teams of adults and the Partners in Play team see it over and over among the kids and adults at Faison and Arsenal.

What if these experiences could be available to everyone in the Pittsburgh region? That’s been the goal for nearly a decade.

The Playful Pittsburgh Collaborative launched in 2014, and their work has included advocacy campaigns in support of recess and the creation of Pittsburgh’s annual Ultimate Play Day, along with the grant-making program Play for Change. On Sept. 16, the Playful Pittsburgh Collaborative will participate in the first National Day of Play through the International Play Association USA.

Meanwhile, The Grable Foundation released the publication If Kids Made the City in 2018 to imagine what a more playful Pittsburgh could look like. And Grable’s support for initiatives like Remake Learning’s Moonshot Grants have catalyzed projects like Partners in Play.

With funding from the Richard King Mellon Foundation, Partners in Play is growing to include a workshop series designed to help even more teachers around the Pittsburgh region discover ways to incorporate playful learning. These in-person workshops (recorded so that more teachers can watch them at a later date) will likely cover topics like:

- How to create community in the classroom through play

- How to integrate math and literacy skills and practices into a play experience

- Harnessing the making and creativity component of play

“We’ll be offering this workshop series in the spring,” Merenstein says, “to really expand the network of educators who are interested in play and play-based learning. And from there we hope to recruit more educators to join us in Year Two in fall of 2024 to incorporate and prioritize Playlab and those play-based learning practices into their school day, as well. So we hope to expand that cohort to around 30 educators.”

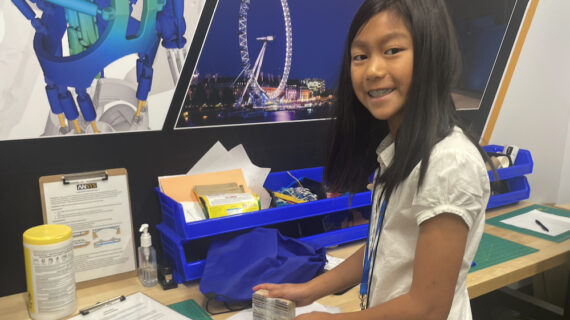

But what about extending play far beyond the walls of K-12 schools?

Beginning this fall, The Grable Foundation and Henry L. Hillman Foundation will partner with the Playful Pittsburgh Collaborative and Remake Learning to launch a new grantmaking initiative called Let’s Play, PGH! to help regional organizations promote intergenerational playful learning in public spaces.

This invite-only, multi-year grant opportunity offered to about two dozen regional organizations includes several rounds of funding for the design, testing and implementation of community play concepts. Funding will range from $4,500 for planning to $150,000 for full-project implementation.

The Playful Pittsburgh Collaborative’s Adam Zahren, who serves as project manager for Let’s Play, PGH! says the key is centering community feedback. Far too often, Zahren says, even well-meaning initiatives take a top-down approach.

“It’s, ‘we’re going to come in, and we’re going to make your community better and we know what you need for your community.’ But in reality, the community knows what the community needs. And if the community doesn’t feel like they’re a part of the planning process, they might not be interested in whatever design comes out of it,” he says. “So part of this grant process is really that community feedback piece in getting iterative feedback.”

Rao says that can happen even within schools.

“Post-pandemic, there’s quite an inequitable attitude towards children from low-income and under-resourced neighborhoods, that they need more of the academics,” she says. As a result, “in the schools that we’re working with, there’s a deficit of play.”

Everyone needs play, now more than ever. So Let’s Play, PGH! aims to infuse it into the Pittsburgh region in ways that really serve individual communities. To kick off this work, the invited grantees gathered on August 28th for a workshop led by Sarah Wolman.

The goal, Zahren says: “Learning about playful learning landscapes and having the opportunities to prototype different playful learning landscapes out of cardboard and other crafting materials.”

In the days leading up to this daylong session of play and creativity, Zahren’s office was overtaken by cardboard boxes and crafting supplies. But he was more than grateful for the inconvenience.

“I’m really excited to see how folks engage with people to create something that is beneficial for their community,” he says, “but also for Pittsburgh at large.”

To Bindewald, nothing is more valuable right now than a group of people spending the day creatively playing and exploring in an effort to make the world an even better place.

Play can teach us. It can help us manage our fears and even “unlock and uncover the most amount of good” for a place and the people who live there, he says. And given a chance, “playing and exploring can become a way of life.”

Want to know more about playful learning? Check out this Q&A with Sarah Wolman.