Take a fascinating tour of the teenage brain with Pittsburgh researcher Dr. Beatriz Luna

Teens everywhere ignored the coronavirus shelter-at-home edict and joined their friends at the local park, either unaware or defiant of the need for social distancing.

College kids flocked to Florida beaches for spring break early in the public health crisis, sending shock waves over social media platforms where the photos and videos went viral.

And adults everywhere asked: What could they be thinking?

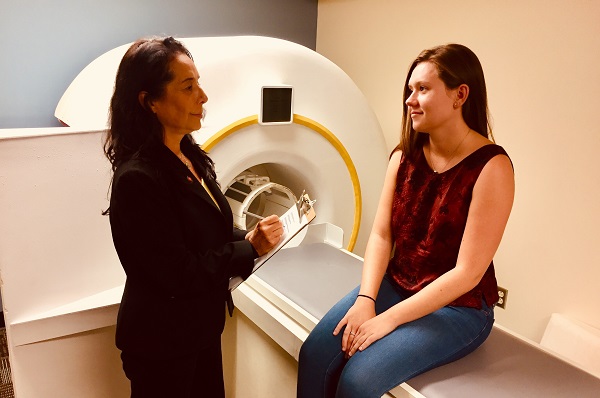

Dr. Beatriz Luna understands the teens’ behavior. The University of Pittsburgh professor of psychiatry studies the brains of adolescents and young adults. She says we shouldn’t be surprised at their need to engage in risky, sensation-seeking behavior. Quite simply, they learn through experiences — good and bad.

“We’ve really been interested in the transition from adolescence to adulthood for many reasons,” says Luna, of Highland Park, the director and principal investigator at Pitt’s Laboratory of Neurocognitive Development. “People think of it as a broken-down part of the lifespan — these crazy teens — but in fact, it is how individuals can gain that new experience that will help them gain independence as adults.”

Adolescence also is a time when psychiatric illnesses start to emerge, so studying young minds can help to understand brain-based changes. Adolescence begins around age 10, and there’s some evidence that the brain may still be developing much longer than previously thought, into one’s thirties, Luna says.

At any given time, Luna has around 200 young people enrolled in studies that are ongoing at the lab, following them sometimes for years. She recruits adolescents and teens through advertising, word of mouth and partnerships with the city and schools. They’re paid a fee, typically $250, to come in and perform actions such as playing a computer game while hooked to an MRI and then an EEG. They return 18 months later for a follow-up.

In addition to her work at Pitt, Luna is co-investigator with Pitt’s Duncan Clark for the Allegheny County Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, a $300 million National Institutes of Health initiative for which Pittsburgh is one of 24 sites. Researchers across the country are studying 11,000 youths, ages 9-19, to understand how their brains change.

Critical development

“We’re looking at a sensitive period or critical period,” says Luna. “Adolescence is a time when things are really shaping in a way that they’re not shaped at any other time in the lifespan. Things that are occurring in adolescence will determine who you are. You’re born with a neurobiological genetic disposition; it’s who you are. Your particular environment, that’s predisposition. The system is trying to fit and adapt to the demands of the environment. When adolescence comes, it’s a time when the brain says, ‘OK, we’re going to figure out what you’ve been using and haven’t been using.’”

Teens typically act on impulse and sometimes against their better judgment, she says, because the brain seeks reward to enhance their emotions. However, even though reward and emotion win over cognitive decisions, Luna’s research shows that a teen isolated in the laboratory without the influence of friends “can demonstrate adult-level cognition, though we still see elevation of reward and emotion.

“What we are thinking is that adolescence actually is a time when everything is there,” Luna says, “including decision-making abilities, but it’s driven by heightened reward, sensitivity and emotion. It could be seen as a way for the brain to say, ‘OK, I’ve given you everything. Now I’m going to give you a big push — go and make decisions.’”

Luna doesn’t like using the word “imbalance” or other terms that might suggest there’s anything wrong with adolescence. “It has its own particular balance,” she says. “You’ve gotten hold of adult-level, executive functions but they’re being driven by reward and emotion. It’s like learning how to drive: it can be undermined by having peers around, getting super excited.”

Action and consequence

Sometimes her studies seem deceptively simplistic — for example, the anti-saccade task, where she’ll instruct a teen not to look at a light that pops on.

“They look at the light. They’ll say, ‘I know what you wanted me to do, but I was not able to.’ When they do it correctly, they use the prefrontal cortex,” she explains, which relates to planning complex cognitive behavior and decision making. “When they do it wrong, an alarm system in the brain alerts them. In adolescence, we don’t see that alarm sounding off at the same volume as adults. … This alarm doesn’t go off because then you wouldn’t be trying new things.”

It may help parents to know that engaging with a teen — talking with them about right and wrong and the consequences that may follow actions — can make a difference in their decisions.

“There’s a lot of variability in how the brain is being engaged when asked to do an executive task,” Luna explains. “There’s a lot less variability as you become an adult. With sensation seeking, the brain is doing that as well — it’s experimenting and trying different ways of being able to generate executive behavior. … An adolescent talking with an adult, without distraction, can access their executive system — they’re owning it.”

It’s important, too, for parents, teachers and others who work with young people “to recognize that they have this heightened drive toward short-term rewards,” Luna says. “That is something to take into consideration if you’re thinking of distraction, but also could be used to leverage what they’re going to do. If I say, ‘Don’t look at the light,’ if you give them a reward, magically they can do it right.”

She tells parents to inform their kids about possible outcomes – even if you can’t stop their reckless behavior. Adolescents are shortsighted, but you can give them the long-term effects of what could happen.

Sensation-seeking is normal and it’s going to happen. “I was a crazy adolescent, too, but here I am,” she says. “Keeping the door open is so important, so they know they can come of their own volition to seek help if they need it. You’ll be talking to an adolescent, and they act like they don’t care, but the brain can’t help but process that information. Don’t give up, even if they’re giving you that scowl.”

Homegrown research

Luna’s work with young people started coincidentally when her own son and daughter reached adolescence. Her husband, Dennis Childers, is an artist and musician who teaches at Pittsburgh CAPA.

“We have great conversations. He always says there’s that summer, typically 9th grade, when [students] come back and they’re totally different,” she says. “He knows how to talk to teenagers so well. He’s had a lot of kids who have come up and said to him, ‘I’ve been told I’m good for nothing,’ but my husband sees talent in all of them.”

Above all, Luna believes in giving adolescents a fair chance.

“Adolescence is not a disease. It’s an amazing time of life that we have to understand so we can make it the best possible,” she says. “The potential there is amazing because that’s going to determine the boundaries of who you are as an adult.”

This story is part of the Kidsburgh Mental Health Series funded by a grant from the Staunton Farm Foundation. The Foundation is dedicated to improving the lives of people who live with mental illness or substance use disorders. The Foundation’s vision is to invest in a future where behavioral health is understood, supported, and accepted.

Other stories in the series include the Kidsburgh Mental Health Survey report, insight as to how parents can deal with coronavirus anxiety and advice on remaining resilient during times that try your family’s mental health.