The people and places fighting childhood hunger in Pittsburgh

A quick drive through Pittsburgh’s East End would be enough to convince any bystander that our city is undergoing an economic boom. But despite the rapid takeover by luxury condos, high-end shopping and fine dining establishments, we have a dirty little secret. Our kids are hungry.

According to the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, an estimated 20 percent of children in Allegheny County are considered food insecure. And Pittsburgh is not alone in this problem. Feeding America reports that over 15 million children nationwide are unsure of where their next meal will come from.

The consequences of this public health issue are devastating. These kids are at an increased risk for a variety of physical and behavioral health issues. They are five times more likely to commit suicide in their teen years. They are three times more likely to be suspended. They are twice as likely to repeat a grade in school. And their long-term prospects are just as dismal–with increased job turnover and chronic absenteeism rates throughout their lives.

The statistics are surprising, sad . . . and catalytic. In honor of National Hunger Action Month, we have spent the last few weeks getting to know some of the people and places fighting childhood hunger in Pittsburgh.

Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank

We started our journey at the headquarters for the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank. Located just past Kennywood in Duquesne, this LEED-certified building is the central storehouse for the 26.5 million pounds of food that are redistributed annually to community food pantries, emergency shelters, soup kitchens, after-school programs, summer feeding programs and more throughout the region. The size of its operation reflects the scope of the issue.

“There are over 45,000 children in our own county–right here in our own backyard–who are food insecure,” says CEO Lisa Scales, who has been with the Food Bank since 1996. Nearly 76,000 children and over 150,000 households are fed annually by member agencies that get their food from the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank.

Scales also oversees the other Food Bank initiatives, including many that directly impact the issue of childhood hunger. An important one is the Southwestern Pennsylvania Food Security Partnership.

Southwestern Pennsylvania Food Security Partnership

The mission of the Southwestern Pennsylvania Food Security Partnership (The Partnership) sounds straightforward–to significantly reduce hunger in our region. But The Partnership and its director, Karen Dreyer, have dedicated years of research and networking to figuring out how to systemically achieve its goal.

Their findings reveal one important point–food insecure children in our region are actually underutilizing the programs that already exist to help them.

For example, participation in the federally-funded Summer Food Service Program–which provides free breakfast and lunch to food insecure children throughout the summer months–has waned. Why? Because kids can’t get to the food distribution sites.

In response to this finding, The Partnership recently worked with students at Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College to introduce a data-driven approach to boosting participation in the program.

“We had the students create a map that used census data on where the highest number of low-income kids were located with the fewest summer food sites,” says Dreyer, who explains that their results informed recommendations for new summer food sites at important community hubs for kids.

Grub Up Pittsburgh

Thanks to The Partnership’s data, the region was able to more strategically place its summer feeding sites. But another barrier to participation still persisted: stigmatization. How could we get kids to actually want to get free food without feeling judged by their peers? The City of Pittsburgh and Citiparks launched the GrubUp Pittsburgh program this past summer to help.

“GrubUp is about normalizing the experience of getting free food in the summer,” says Dreyer, who explains that the name–GrubUp–replaces the conventional “feeding program” terminology with something that sounds more trendy to kids. GrubUp also uses an easily navigable, mobile-friendly website to help kids locate food sites on their devices.

Finally, the program introduced fun activities during meal times to make the experience more enjoyable. Kids prepared green smoothies and veggie quesadillas. They dissected lima beans. And perhaps most movingly, they decorated paper plates with messages about childhood hunger to send to elected officials (photo above).

This summer GrubUp successfully delivered free breakfast, lunch and afternoon snacks to youth at more than 125 locations across the city and even mobilized a food truck to reach more. And on September 21st, GrubUp will launch a similar after-school program.

Focus Pittsburgh

Thanks to federally-funded programs like the School Breakfast, School Lunch and Summer Food Service, kids can generally get something to eat on weekdays. But what about when they go home for the weekend?

Paul Abernathy is the director of Focus Pittsburgh, a community development organization in the Hill District. About four years ago, he started to hear about children at the elementary school next door who were going hungry over the weekend.

“We weren’t sure about the scope of the problem even though we live right in the community,” explains Abernathy. “So we mobilized parents to help us find the families that were most in need.”

These parents identified about 50 children, and Focus Pittsburgh started sending food-filled backpacks home with them on Friday afternoons. But the need just kept growing. “Every week we were finding more and more kids who were food insecure,” says Abernathy.

Focus Pittsburgh now runs the largest and most organized backpack feeding program in the city and, this year, hopes to feed about 2,000 children in the Hill District, Hazelwood and the Northside. Backpack feeding programs like those run by Focus Pittsburgh and the Homewood Children’s Village have catalyzed similar programs at local schools, including the Linden Backpack Initiative run by Tara McElfresh at the Point Breeze elementary school.

While increasing access to federally-funded programs and backpack initiatives can be very helpful solutions, childhood hunger can be a symptom of deeper equity issues that need to be addressed also.

412 Food Rescue

“Hunger is not a supply problem. It’s a distribution problem,” says Leah Lizarondo, a local food justice advocate and cofounder of 412 Food Rescue. “Nearly 40 percent of our food goes to waste in this country, while one in six goes hungry.”

412 Food Rescue addresses the so-called “long tail” of hunger, meaning food waste is often in the form of small quantities at the retail level. Think of your favorite local grocer. What happens when their produce is mislabeled? It generally gets thrown out. Think of your favorite local restaurant. What happens when the kitchen closes at the end of night? Food gets thrown out. Until now.

Lizarondo and her cofounder, Gisele Fetterman, have worked with developers to create a soon-to-launch mobile app that will address this issue.

The app functions similarly to Uber. A local grocer, restaurant or caterer will input into the app that they have food available for donation. A volunteer will then be notified via the app to pick up this food. This volunteer will then bring the food to a destination–like a soup kitchen, a shelter, a Head Start Program, an after-school program, etc.

The food will be only perishable items–nothing canned or processed–and will be obtained at no cost and given at no cost. “We are able to reach food and transportation deserts where residents cannot even get to a pantry. We bring the healthy food to them,” says Lizarondo.

Just Harvest

Lizarondo brings up the idea of food deserts–or parts of the city without easy access to fresh fruit, vegetables or other healthy “whole” foods.

According to a report commissioned by local nonprofit Just Harvest, an estimated 47 percent of Pittsburgh residents reside in these food deserts, with over 70 percent of these residents being low-income. In fact, when compared to cities of similar size, Pittsburgh has the largest percentage of people living in food deserts.

The report also highlights several key strategies for improving access to healthy food in Allegheny County, including bringing full-service grocery stores into these food deserts and adopting food stamp payment systems at local farmers’ markets and farm stands.

In response, Just Harvest launched Fresh Access and Food Bucks–two programs designed to entice food stamp recipients to buy fresh produce at local farmers markets. Families can use their EBT cards to receive tokens from on-site kiosks. For every $5 they spend on fresh produce, they get an extra $2.

Citiparks Farmer’s Markets were the first to adopt Fresh Access–but the program has expanded to include 15 markets citywide thanks to help from other community stakeholders, including the Pittsburgh Food Policy Council. Approximately 50 percent of Fresh Access users have children under age 18 in their homes.

Grow Pittsburgh

Grow Pittsburgh is another organization boosting food security in underserved communities. Grow Pittsburgh’s Allegheny Grows program provides education, planning resources and technical assistance to create vegetable gardens in low-to-moderate income communities in our region.

“The amount of produce that can be grown in a community garden is pretty astounding,” says Julie Pezzino, who started the community food garden program during her six-year tenure as executive director of the organization.

Pezzino also oversees the school garden program, where children get their hands dirty learning how to grow their own gardens. “We’re providing kids and their parents with information about how to grow and cook healthy foods and giving these families the tools to have better nutrition in their homes,” says Pezzino.

But what does healthy eating have to do with fighting hunger? Pezzino makes the counterintuitive connection between childhood hunger and the obesity epidemic–a link stemming from the affordability and accessibility of unhealthy foods in these so-called deserts.

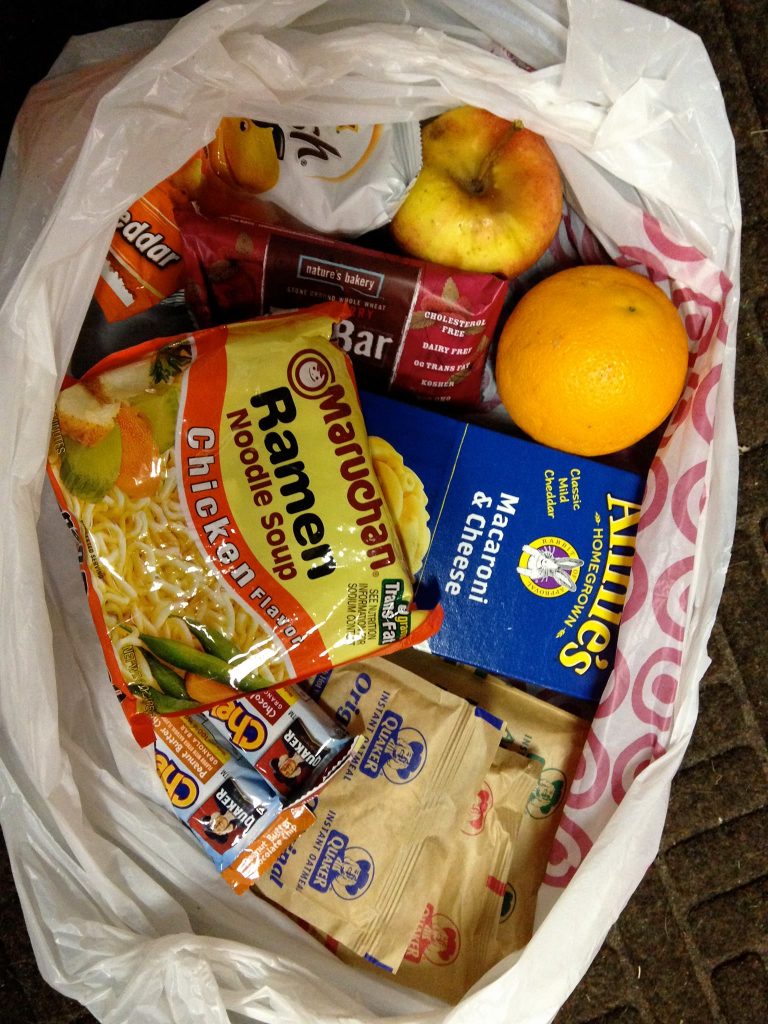

“What’s available in these lower income communities is ample food that isn’t necessarily good for you. It’s all the processed stuff. If the fruits and vegetables are expensive, of course you’re going to choose the ramen over the tomato,” says Pezzino, who empowers these communities to realize they have another choice–to take the soil into their own hands.

Although we know there are many more faces and places impacting childhood hunger in Pittsburgh, our tour has come to an end. Want to do your part to help? Check out this calendar created by Social Venture Partners to find ways you can fight childhood hunger this month and beyond!

Featured photo: Summer Food Service program, Photo courtesy of Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank