Photo essay: Playful Pittsburgh Collaborative explores a day of play to support learning and harness creativity

This essay was written by Sarah Siplak, director of the Playful Pittsburgh Collaborative, with photos by Nico Segall Tobon.

On Oct. 30, educators and community builders from across southwestern Pennsylvania and northern West Virginia gathered at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood to explore how play can be used to build community and support learning. The Playful Pittsburgh Collaborative, a group of organizations dedicated to advancing the importance of play in the lives of children, families and communities in the Pittsburgh region, co-hosted this unconference event with Trying Together, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, and Philadelphia Playful Learning Landscapes.

The event was a call to action to harness play in service of building community. For many, it was the first opportunity to gather with colleagues after the mass shooting at Tree of Life Or L’Simcha synagogue. And while participants processed that tragedy collectively throughout the day, the healing power of play was present.

Nearly 100 participants spent the day playing and learning together, discovering how play unlocks concepts for young learners, helps adults find new perspective, and has enormous potential to benefit everyone when it’s used to solve problems in our communities.

What’s the creative potential of play? The process of playing your way through different possibilities, learning and discovering along the way, and producing unexpected results.

That was the heart of what keynote speaker Sarah Wolman from The LEGO Foundation called “the LEGO idea.” Did you know that a set of six 3-inch-by-2-inch LEGO bricks can be combined in over 915 million different ways?

To demonstrate this creative potential, Wolman asked each attendee to use a set of LEGO bricks to build a duck in 30 seconds. 100 different attendees each produced 100 different ducks. Some ducks could stand, others had to sit. Some looked to be in flight, others at rest. There was no model duck everyone was trying to recreate. Instead, attendees had to access their own creativity, spatial capacities, and executive function to make their own vision for the duck real. The experience reminded attendees of what it means to play to learn.

In her talk, Sarah Wolman grounded the group’s thinking in the five domains of child development: Physical, Emotional, Social, Creative, and Cognitive.

She pointed out ways that learning through play builds skills across these domains. Through physical play, children develop spatial awareness. That spatial awareness, combined with the creative, cognitive, and collaborative challenge of solving a puzzle with your peers, helps children develop spatial reasoning, an important precursor to math skills.

To make these insights real, she challenged attendees to work together to build a bridge out of LEGO bricks that could span across signs sitting in the middle of each group’s table. As with the duck-building exercise, no two groups built the same bridge. Different this time, though, was the setting and intention of the exercise. Instead of expressing just your own idea of what a duck looks like, this challenge involved learning in a social context where communication, collaboration, and negotiation were key.

To reinforce the link between play and emotional development, Sarah Wolman made special reference to dramatic play, the kind of play where children take on roles, act out scenes, and learn by becoming (also known as make believe).

“Dramatic play is a powerful way to develop tools for learning,” she said. “When children engage in dramatic play, they’re practicing the skills of being high-functioning adults out in the world, negotiating and navigating those situations.” She referenced studies showing that when children act out what they read, their reading skills “go through the roof.”

Make believe play often involves symbolic representation: deciding that one object can stand in for another. This is a learned skill that children, especially pre-verbal children, can develop through play. Before children can read or write, which requires they understand that the letter A symbolizes a sound, they start to develop foundational capacities for symbolic representation.

To demonstrate how this happens through play, Sarah asked attendees to use a random assortment of LEGO bricks to create a self-portrait.

Childhood today is different than it was 20 years ago. So what does that mean for play? That was the frame set by Jennifer Zosh, Ph.D., Pennsylvania State University Brandywine Campus.

Jennifer identified children’s innate drive to play as one of their greatest assets in making sense of “today’s weird childhood and tomorrow’s unknown future.” And it’s not just kids who can use play to navigate uncertainties: adults, seniors, even animals rely on play as equal-parts coping skill and learning modality.

But, Jennifer noted, when people think about the concept of “play to learn,” they tend to lean into their own personal vision of what play is. One person may think sports are quintessentially play. Another person may picture a board game. A third person may think of improvised storytelling. “We need to get better at understanding play as a spectrum,” Zosh said. Under the umbrella category of “Playful Learning,” she identified three main types:

- Free Play in which the child leads and learning is latent (as opposed to intentional).

- Guided play in which the child still leads, but an adult scaffolds play toward a learning goal.

- Games that are designed and/or led by adults with enforced rules and constraints.

The morning featured lightning talks from playful people from across the state of Pennsylvania.

Marilyn Russell, from left, curator of education at the Carnegie Museum of Art, shared how a visit to the art museum can be “intrinsically motivating, involving active engagement, and resulting in joyful discovery”—which just happens to be a commonly accepted definition of play. Natalie Potts, associate curator of education at the museum, described how that comes to life in the museum’s education programs, which create a space for students to question the world around them: not just a “how to” class, but also a “what if” class.

Molly Schlesinger, a postdoctoral fellow at the Temple University Infant & Child Laboratory, shared how Philadelphia Playful Learning Landscapes uses play in out-of-school contexts to infuse irresistible, convenient, and effective learning spaces right in the urban landscape: human-sized board games at the museum, rock climbing walls at the library, puzzle walls at the bus stop, and much more.

Medina Jackson, director of engagement for the PRIDE Program at the University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development, asked the group “What’s a tired parent to do? When it’s late and your child says ‘Mama, will you play with me?’” and shared how play creates the space in which growth can happen—not just for children, but for the adults in their lives, too. She left the room with a simple mantra: “today, I will play.”

Camila Rivera-Tinsley, director of education at the Pittsburgh Park Conservancy, demonstrated the connection between environmental stewardship and play, showing how open-ended experiences in Pittsburgh’s parks have led to a more resilient, environmentally-literate population.

Over lunch, participants had a chance to get serious about their play, by (of course) playing. Members of the Playful Pittsburgh Collaborative partnered with Philadelphia Playful Learning Landscapes to hold a mini-Ultimate Play Day and Ultimate Block Party inside the museum’s Hall of Architecture, where participants hunted for treasure, played a spelling game called Human Scramble, tried out a new kind of hopscotch called Jumping Feet, and much more. Will Tolliver (center), Manager of Early Childhood Learning at the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh, visited the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust’s activity, where he created his own wearable art out of reused bubble wrap.

Events like these, which the Playful Pittsburgh Collaborative hosts annually, invite community members to play together and raise awareness of the benefits of play for everyone—from birth to 199 years old. The event is held outside in a different community each year, and is a great opportunity to see the power of play in action. Stay tuned for the next Ultimate Play Day in May 2019!

Play can involve a good deal of uncertainty and a fair amount of risk. When an activity has an uncertain outcome, we’re drawn in to find out what’s going to happen. When the possibility of risk is present, we pay closer attention and focus all of our senses. Both these conditions help us take more responsibility and ownership of an experience. But according to Alex Gilliam of Public Workshop and Tiny WPA, we have made our built environment so free of risk and uncertainty that we (both adults and children) are more apt to be drawn in by our mobile phones than the real-life opportunities for play that surround us.

Alex works with young people and communities who want to turn this trend around and make play an everyday possibility in our everyday lives. He shared stories of young people, families, and senior citizens finding and fixing problems in their communities by embracing uncertainty, risk, and yes, play. Alex shared stories of communities building bus stops that double as jungle gyms, dance stages on street corners, ergonomic benches for the elderly, and adventure playgrounds in public housing facilities.

The approach is all about giving young people opportunities to solve for themselves, or as Alex put it: “Play is not just our product, but a core piece of our process.”

Over the course of the day, participants were asked to stretch their minds and their bodies and to dwell in the spirit of play. Working together in teams representing communities in Pittsburgh, southwestern Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, participants included teachers, librarians, school administrators, museum educators, community organizers, after-school educators, artists and builders, outdoor enthusiasts and public policy experts. What they shared in common was a belief in the power of play as a catalyst for community.

Afternoon lightning talks explored how play can be harnessed to help communities thrive.

Danny Mortensen, from left, analyst for programs and operations at KaBOOM!, described his organization’s journey in discovering that simply building playgrounds isn’t enough to foster equitable play—in order to give everyone access to play, they find ways to incorporate play activities into everyday places, from laundromats to alleyways.

Aurora Ortiz, community engagement coordinator for All for All, shared how play can be used to break down cultural barriers, describing her own experiences as an immigrant and the ways in which play helped her build connections that bridged language differences and cultural chasms.

Ernie Dettore, education consultant and a longtime advocate of play, described how play can be used to promote health and wellbeing not just for youngsters, but throughout the adult lifespan. Adults have the opportunity to reframe their free time and play time to make play a lifestyle choice.

Sarah Siplak, director of the Playful Pittsburgh Collaborative, shared their unique model for advocacy—harnessing the collective power of organizations to advance play for and with communities. Sarah shared lessons learned from recent Collaborative projects, including the Hazelwood Play Trail and the Recess Advocacy Team, and offered the Collaborative as a resource for attendees looking to use play to make change.

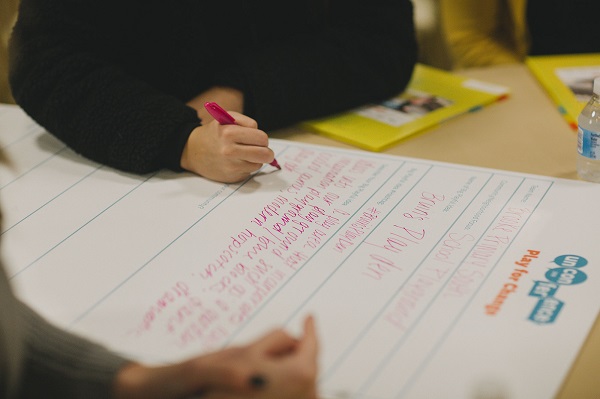

At the end of this inspiring, informative, and playful day, participants put their new knowledge and perspective to work by answering the question “What’s your Big Playful Idea for making change?”

Teams of participants worked together to imagine how play could be used to improve their community. Completing posters together, they explored how their “Big Playful Idea” could help their community, what partners they might need to make it happen, what potential challenges they might run into, and what the next steps would be for making their idea real.

The change-making didn’t end when participants left the museum! At the end of the day, the Playful Pittsburgh Collaborative announced the Play for Change Grant opportunity, a brand new grant program to help conference participants take their Big Playful Ideas and make them into real change in their communities. Grant funding of up to $7,500 is available for conference attendees for projects that are collaborative, playful, uplifting, and accessible.